I've undertaken to play seriously with all the French-speaking F.I.s on the market (and any interesting ones I find in English), in order to derive usable transcripts for their authors and reviews for publication on the IFDB.

Here are a few I've written so far:

Éric Forgeot - Les Méchants meurent au moins deux fois

Éric Forgeot - Le Scarabée et le katana

Nicolas Pérot - Irrésistibles possessions

Benjamin Roux - Interra

In addition to these necessarily short IFDB reviews, I intend to publish commented transcripts of my games here. They'll range from very concrete things like typos (always useful for the author, even if he doesn't take any other remarks into account) to theoretical questions about game design specific to IF, code points (in Inform 7 specifically), etc.

Benjamin Roux - Interra

In addition to these necessarily short IFDB reviews, I intend to publish commented transcripts of my games here. They'll range from very concrete things like typos (always useful for the author, even if he doesn't take any other remarks into account) to theoretical questions about game design specific to IF, code points (in Inform 7 specifically), etc.

I'll begin with Morne Lune, by Balrog.

*

Beyond the game-by-game review, I've embarked on a broader, more analytical approach, which I'm not sure exactly what purpose it serves, except for the pleasure of pure knowledge: I've started, based on the solutions provided on the IFDB, to count the number of verbs needed to complete each French-speaking game, possibly related to the length of the game (the number of commands needed to reach the end).

I'll then be able to rank them, and determine which is the best F.I. from this point of view (which is only one of many, of course). It'll also be interesting to note which verbs are the rarest, the most "exotic", which verbs Inform understands but which NO game uses, and so on.

*

Speaking of reviews, Monsieur Bouc published a little article about La libération these days:

https://mbouc.gitlab.io/blog/test/2019/08/25/La-Lib%C3%A9ration-par-St%C3%A9phane-F.html

I was sure I'd read in it, the first time, a passage about "useless" actions in the game, useless but serving to characterize the character or set the mood. Maybe he took it out. Maybe I was dreaming. In any case, it made me rethink something that seems to me more and more to be one of the great truths of game design, specifically in the field of FI.

– We're here to tell stories. To build narratives. In absolute terms, not to propose environments to the player where the main goal and the pleasure of the game would consist in searching every container, lifting every piece of scenery to see if something is hidden underneath, without any real justification but to "see what's going on" out of curiosity or, worse still, because you're blocked in your progress. If the character needs to find an object under the desk, he or she must of course be able to do so because the player has spontaneously typed "look under the desk". But he also needs to be able to find it by bending down because he dropped his lighter after the player typed "smoke a cigarette" – or after any other banal, useless, roleplaying action. Because that's how things happen, in life. And in novels, and in movies. F.I. should be no exception if it's to be anything other than a simple pretext for puzzles.

– Nor are we here to provide novels in kit form, to be read in fragments without actually doing anything in the game. That's a mistake I made with L'Observatoire (contest version), where there's virtually nothing to do, either for the character or the player, other than click on links that give information about the game world. To a certain extent, I may also have overused the verb "to think" in The Storm. The saying goes: "Show, don't tell". A scene, an NPC, a dialogue, an object... are better vessels of information about the game world, than a pavement of text (as we often endure in spades at the start of an RPG game). To this we might add that all information about the world must follow an action by the player-character, whether useful or a mere pretext, as in the example above.

The unavoidable digression

The unavoidable digression

Another of Monsieur Bouc's criticisms of my games in general, which he mentioned to me privately, is my tendency – in L'Observatoire as in La libération – to anachronisms and stylistic breaks. I personally don't feel these anachronisms, or rather they don't shock me, since it's always been clear in my head that I'm dealing with a world that is neither the present-day world, nor a post-apocalyptic world, nor the 1940s, nor the 19th century, but a mixture of all these, It's a mixture of all these things, not a recipe for yet another imaginary world – I'm not at all into steampunk, dieselpunk, etc. – but simply the way my imagination works, where seemingly contradictory things coexist peacefully. I can mention, in a description, guards armed with halberds, and later talk about the metro, without this sounding to me like a deliberate, calculated anachronism; it's more like an absence of time, as indeed in the workings of everyone's unconscious.

*

I realized while playing various CPC games these days, some of which I had played as a child, that these anachronisms, to call them that, probably came partly from my own memories as a gamer.

The unforgettable SRAM 2, for example, uses anachronisms (an elevator that leads to the top of a tower, allowing you to see the surrounding area; a motorboat that allows you to explore the moat of a castle) and contrasts, or breaks in tone, to poetic effect, helping to create an atmosphere of wonder, humor and adventure.

*

In a game like Le Nécromancien, which I didn't play as a child but which is more or less similar to Ténèbres, which I had tested, we find something even more interesting for what interests me today: the naive, unintentional anachronisms; the breaks in tone that owe nothing to design but simply to a certain clumsiness on the part of the author, and which ultimately give the game an unexpected charm.

We're not talking about big anachronisms here: you don't come across a motorcycle in the middle of a medieval setting. It's less a question of set elements or objects than of vocabulary – you'd rarely expect to come across "concierges" and guys out for a "drink" in a fantasy game, and that's what gives Le Nécromancien its charm, that very slight impression, almost unconscious as you play, of being in a rather vague temporality, neither contemporary nor entirely medieval, neither in the real world nor in a 100% fantasy world.

We're not talking about big anachronisms here: you don't come across a motorcycle in the middle of a medieval setting. It's less a question of set elements or objects than of vocabulary – you'd rarely expect to come across "concierges" and guys out for a "drink" in a fantasy game, and that's what gives Le Nécromancien its charm, that very slight impression, almost unconscious as you play, of being in a rather vague temporality, neither contemporary nor entirely medieval, neither in the real world nor in a 100% fantasy world.

*

My old friend Xavier recently told me that the photos of my little vacation in Troyes reminded him of the illustrations in the old Warhammer RPG edition he has at home. This surprised me all the less (I'm talking less about the comparison itself than about the thought process) as I myself have always been fascinated by the graphics of Fer & Flamme, for example, because they reminded me of the alleys and old houses of dilapidated Alsatian towns and villages not far from home.

Or was it the other way around? Or, as with the chicken and the egg, there's no answer to the question of order. Places in fiction and places in reality are in continuous exchange, in constant dialogue in our minds. Time doesn't exist. The real world is a patchwork of temporalities, and refers to fictions set in different eras; the fictions themselves refer to the real world.

*

I've been playing Saga again, still on CPC, for the last few days. I'd forgotten just about everything about the game, except that I'd liked it and that its scenery had left an impression on me as a child, because although it was set in a medieval world, it reminded me of my own real world, my immediate environment.

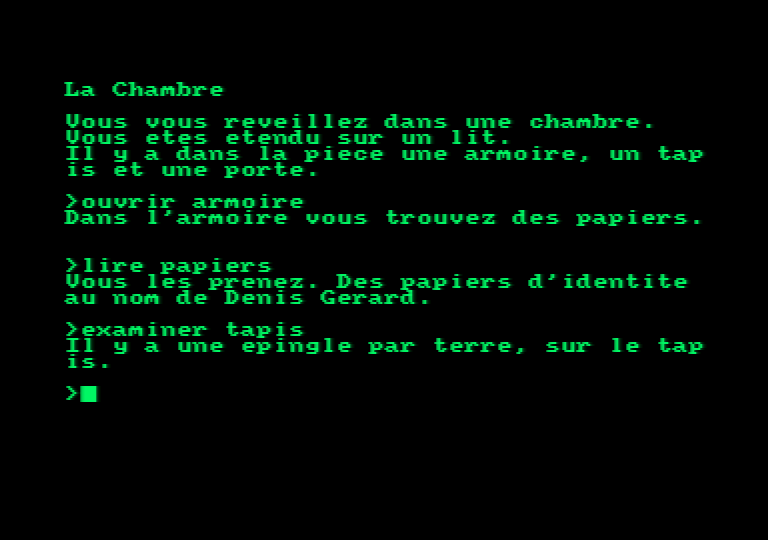

The image above reminded me, as a child, of the Vosges, where my parents used to take us on vacation. In passing, I realize that these black drawings on a green background also remind me of some very old regionalist magazines, full of old folk engravings, which intrigued and even fascinated me as a teenager (that's how much of a nerd I've been for a long time) and which were, precisely, usually printed on cheap, greenish paper.

A few news (bis)

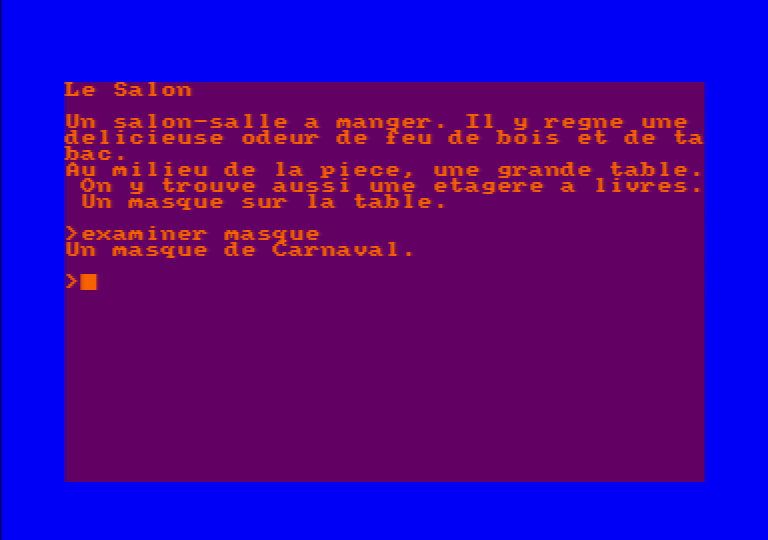

Speaking of CPCs, I've already mentioned here a game I started as a teenager, at 15 to be exact, called Les Masques du Carnaval.

There's nothing so "medieval" about these views of an old village. A decrepit cemetery wall, a dirt road, houses in the distance. The game could just as easily be set in a backward village in 2019.

This anachronism, which isn't really an anachronism at all, also contributes to the impression, while playing, of not being in any specific era, nor even in any specific universe – neither real world, nor imaginary fantasy world – but in a kind of eternity that is that of memory, of culture, where everything is superimposed.

A few news (bis)

Speaking of CPCs, I've already mentioned here a game I started as a teenager, at 15 to be exact, called Les Masques du Carnaval.

Strange as it is, I'd simply forgotten about it for years and years. I think that even when I became interested in interactive fiction through Éric Forgeot (with whom I'd been making music for years) in 2007, the memory of that aborted game was still buried, unconscious. I had to go through my floppy disks after repairing my Amstrad a few years ago, and find the files, for it to come back to me.

I uploaded the game to my itch.io account:

https://stephanef.itch.io/les-masques-du-carnaval

... but the two main French sites dedicated to the Amstrad, CPC Rulez and CPC Power, have done me the honor of hosting it too:

https://cpcrulez.fr/GamesTest/les_masques_du_carnaval.htm

https://www.cpc-power.com/index.php?page=detail&num=16857

*

I'm continuing to work slowly but relentlessly on L'Observatoire, which is seriously beginning to depress and tire me. The final dialogue between Paloma and the player-character is "long" and complex (or at any rate, very non-linear), and even apart from the technical aspects, what the actual writing requires in the way of stirring up old personal sludge is especially painful.

Someone I had playtest the game in its current version told me it sounded very autobiographical, and I'm well aware of that – in fact, it's probably far too autobiographical. Even if I've added a lot of fiction, even if I've remixed elements of my own life, making them relatively unrecognizable, to build the journey of the player-character and his interlocutor, the whole thing probably inevitably gives off something very personal that can be disturbing to read, or simply uninteresting. Too bad. It'll be my own little Modiano moment.

That said, as I was saying, working on L'Observatoire is painful, and I realize that I'm starting to get the hang of – emotionally – all this stuff about the past resurfacing, hallucinated wandering in the rubble of one's own life, BLABLABLA... and I tell myself that I'll avoid this kind of theme in my next games, at least for the time to come.

*

Working on The Storm made me feel a certain nostalgia for the parser, and made me realize that there was something more engaging – in every sense of the word – about typing commands than clicking on links. You act with your body, and this reinforces the impression of acting in the game.

This intuition was later confirmed in a discussion with M. Bouc, who told me that he found it hard to get interested in L'Observatoire, precisely because he had the impression that he could simply click at random to go from the beginning to the end of the game, and that this technical possibility alone was enough to destroy his involvement in the game. It's a remark that rubbed me the wrong way, but which I immediately understood had to be taken extremely seriously.

*

All this to say that I've started work again on a little game that was my very first interactive fiction project, coded from a draft written to me by Éric Forgeot around 2008 or 2009, when I understood absolutely nothing about Inform and needed someone to get me started.

I started with a simple vision, something irrational that I didn't feel the need to justify to myself: a man wakes up, in a white suit, confused and covered in blood, on a beach at night, outside a seedy sailors' bar.

I'd created a whole town – dozens of rooms – to explore, but I had no idea how to explain this introductory scene, or how to justify, from a storytelling point of view, having the player-character visit all the places, meet all the NPCs, etc., etc., etc.

I'm thinking today, after so many years, and after a detour into hypertext, that this primitive scenario deserves to be revisited, as part of my partial and somewhat more thoughtful return than in my early days (thank goodness!) to the parser. Not just for the sake of it, but because the story itself and the gaming experience I want to convey to the player require the parser.

With a well-defined, well-defined space and temporality, a beginning, an end – in short, something that can be finished, released and played.

*

For a long time, I wondered about the strange effect of "you see, you hear..." in interactive fiction.

It took me ten years to figure it out when I returned to this sketch, with its lost, bloodied character: you're dead or delirious, and the voice speaking to you is there to guide you.

Because that's what we'll be, in this game: a kind of ghost guided by an inner voice – "you're on a beach, you see this, you see that" – who wanders freely through the scenery trying to understand what's happening to him.

For years now, I've had this intuition of F.I. to be parsed as directed dream, waking dream, hypnosis session... so the narrator remained an instance to be specified. Again, who is this voice saying "You see this"? And if my aim is to pay homage to / parody / transcend traditional I.F. enunciation (You see this, etc.) by turning it into a kind of directed dream with the narrator as shaman-therapist, then I have to play the game all the way through and let the player TALK too. Suggest actions that come to mind, like a sick or dying person in bed.

With this game, I'm proposing an answer that finds its intradiegetic justification – it's probably only valid within the framework of my own obsessions, but it's undeniably an answer.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire